More than 200 attended the AFOA conference in January and heard presentations on the attendance to 2 major incidents in the US. The first involved the engine fire involving flight 383 at Chicago O’Hare airport in October 16’ and second told the story of the operation that grew from the actions of a single ‘active shooter’ at FT Lauderdale Airport only a year ago.

The presenters: CFO Tim Sampey of Chicago International Airport and CFO Bob Palestrant of Broward Sheriff’s Office Department of Fire & Rescue Emergency Services, both described in great detail the effectiveness of initial responses to the major incidents and no one could fail to be have been impressed by the stories of professional fire attacks by ARFF crews in Chicago and the first responders of FT Lauderdale.

Source: Chicago Tribune via Alan Lemery

Both presenters described in detail how an initial attendance drew the full capacity from local ARFF crews and stretched airport resources to their limit. In accordance with every airfield’s emergency plans, the next stage of operations following the search and rescue efforts, drew on the multiagency response appropriate to each incident, each led by the respective local authority – the legally responsible body – for the surrounding community and incident recovery. Amongst the many stories of success, interestingly, both incidents experienced a critical point at which operations were adversely affected. During the secondary phase of the incident, both Commanders described communication challenges during the hand-over from local command to the integrated command arrangements implemented by the local authority.

Face-to-face, commander to commander hand-overs were no problem BUT simple transfer of enabling capabilities such as radio channels, incident logging, document control and data sharing proved: challenging at best and impossible at worst.

With the experience and professionalism of today’s responders, we find it simple to describe the phases of an incident as though they will always naturally proceed in logical succession just like the episodes of a binge-watched television series. When episode 5 finishes, episode 6 will immediately follow – when response finishes, recovery commences. Too often in reality however, either circumstances or individual service capabilities result in the equivalent of someone coming in and changing TV channels mid story without telling you! Although we can quickly recover (or so we would have everyone believe…), vital parts the plot can be lost and continuity of command can fracture. Of course, we work hard to overcome the problem and always manage to ‘get by’ but hindsight is the most critical judge and hindsight teaches that this is a recurring issue that we’ve yet to seriously address.

As Fire and rescue commanders, we are often faced with increasing Communication challenges as incidents develop but the last thing we need is an expectation that we will demonstrate our expertise as computer experts at the very time we’re managing an unfolding disaster. There’s a useful phrase that alludes to a solution we’d all welcome “Managing the emergency, not the communications”

Gone are the days where it was sufficient to brief those within our immediate command supplemented with an occasional message over the radio. Communication lines now are increasingly complex and more demanding than ever. Technological advancements drive the expectation for all agencies to not only receive timely (immediate) information but also to be able to interact in real time with command decisions. Whether it’s environmental concerns, the reasonable demands of business continuity plans, air crash investigations or law enforcement, the need to ensure that all agencies are fully appraised of the developing situation on a minute by minute basis is real and the number of agencies requiring information is growing exponentially alongside our growing understanding of the impact of a major incident and the beneficial impact that early involvement of appropriate authorities can have.

Immediate rescue considerations are paramount of course but 10-15 minutes into an incident, the problems of the commander will always be compounded by the need to consider the effects on the surrounding population and the environment as well as the impact that a developing news story will have on the commercial operation of both the airfield and the airline involved. Most importantly, how can the Commander transfer the incredible amount of knowledge and information thus far gathered to the myriad of interested parties now clamouring for that knowledge.

Having usually been present from the initial call, the incident commander will by now inevitably be carrying an enormous amount of information in his or her own head. Broad awareness of ongoing operations and actions are taken so far will have been passed by voice but coordination of the broader information outputs from the incident will be a challenge beyond even the keenest technologist. Info and data streams such as aerial footage, dashcam video from responding trucks, state of the ground, the presence of hazmats, media used, duration of continued operations, weather information, casualty recording and triaging, social media activity, actions taken by all agencies, command structures and decision logs – in fact far too much for any single agency to process. What are the chances of even the smartest commander being able to package that lot into a reliable, recorded and useful hand-over? Experience has taught us that we need some help relating a single unified command picture for incoming resources.

In a perfect World, the next phase of operations would be for oncoming agencies to mirror exactly the communications, data and command structures established in the initial stages – these can then be grown as the number of agencies increase and data requirements become more complex. This would ensure a seamless transfer of incident management information. The reality is that this will never happen – Local Authority and first responder agencies are increasingly geared-up for sharing information with each other on a day-to-day basis. Sometimes they have specified systems together but even where not, they will have procured systems with this need in mind. Experience shows us that that is unlikely to be the case on any but the largest airfields leaving the poor old ARFF Commander as the poor relation at best and at worst unable to participate in modern methods of Multi-Agency working.

Whilst total integration would be an aspiration, more basic interoperability and information sharing capabilities are a far more reasonable and affordable target and one that could be on the agenda of every airfield ARFF operator. Shared command post information, voice integration, logging protocols and even shared hubs for automatic sharing of basic risk and response information would be a great start and all of these are available! Unfortunately, we are still seeing even these basic technical capabilities being over-looked by those specifying both new vehicles and refurbs of existing command capability.

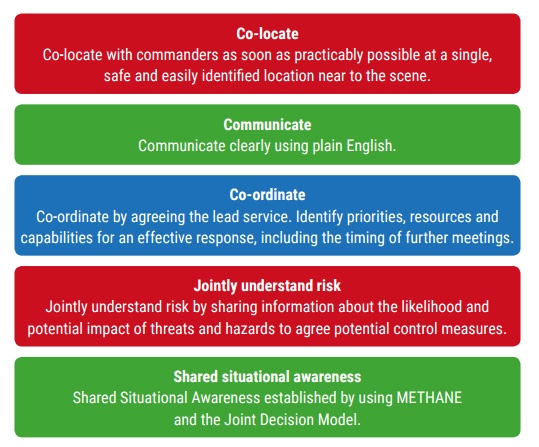

Local Authority responders in the UK increasingly use ‘JESIP’ principles to integrated their decision making processes and communication of outcomes and, increasingly we are seeing them share command software solutions to enable improved transparency between agencies.

There are however, more affordable approaches available – Integration systems go under a number of names and brands but are designed less to replace all current systems but to take many existing technologies and present them through a single interphase or dashboard. Combining digital streams such as video with legacy analog such as legacy voice communications producing a single output available to all responders can massively reduce the burden on the over-stretched Commander at the same time as vastly increasing the information exchange between agencies.

The opportunity now then is for airfield safety operators to mirror some of the capabilities increasingly deployed by Local Authorities around them by ensuring that their responders are using cut-down and affordable versions of what will invariably be deployed on arrival of the broader emergency management and recovery response.

Although there are more suppliers coming into this market space, we are actually witnessing a standardisation of approach whereby multiple diverse data streams are pulled together into a single “dashboard“. An initial look at available solutions can be mind-boggling and confusing but just to mention one component; the most widely deployed solution in the UK AND Middle East currently includes a component developed by ‘Excelerate Group’. With a monopoly on Hazardous Area Medical response and a dominance within the UK fire and Police markets, their “digital dashboard management interface” (DDMI) takes a range of information feeds and data storage capabilities and integrates them into a single presented screen where the operator can rely on the logging and transmission of all information to approved agencies without any direct action on the part of the Incident Commander. A similar solution which majors on voice is designed to integrate analog radio systems. It’s used extensively across the Americas and markets as “BaseCamp Connect”. As they themselves put it; it’s important to allow commanders to “Manage the emergency, not the communications”.

Ignoring the technical or service-specific language used to describe such products, the interesting thing is the critical capability enhancement they can offer ARFF operators. At a fraction of the overall cost of a command system, both systems are vehicle independent and can be deployed in anything from a staff car to a full-scale command vehicle. A massive technical capability uplift without the cost of a bespoke vehicle!

Whichever product is used, the principles remain the same – that airfields will wish to mirror the command information capability of the agencies around them as they will invariably take-over emergency management and recovery as soon as initial firefighting and rescue operations are completed. Airfields should be prepared and equipped to facilitate this hand-over and better able to stay engaged following it.

Whilst airport rescue firefighting technology is reaching new levels of complexity and effectiveness, integrated command & communication solutions are here today and worthy of consideration at all airfields.