Your unit is first to observe a vehicle rollover with ejection. A second vehicle (a commercial bus) has an operator standing next to it. There are many victims in the remaining car, inverted, with several ejected. You communicate with Control to tell them that you need more resources. What are the critical communication points so far? How many patients? What conditions are life threats? Do some of these patients meet the criteria for airlift? Depending on the scene, what hazards are present to the rescuers? Can Incident Command quickly be established to dispatch additional help for you? This individual can relay patient status back to Medical Control to prepare facilities in the area for more substantial interventions.

In Mass Casualty, always evolving as we learn, there are many considerations. Communication and facilitation of resources on the scene are critical elements of Incident Management. There are many others.

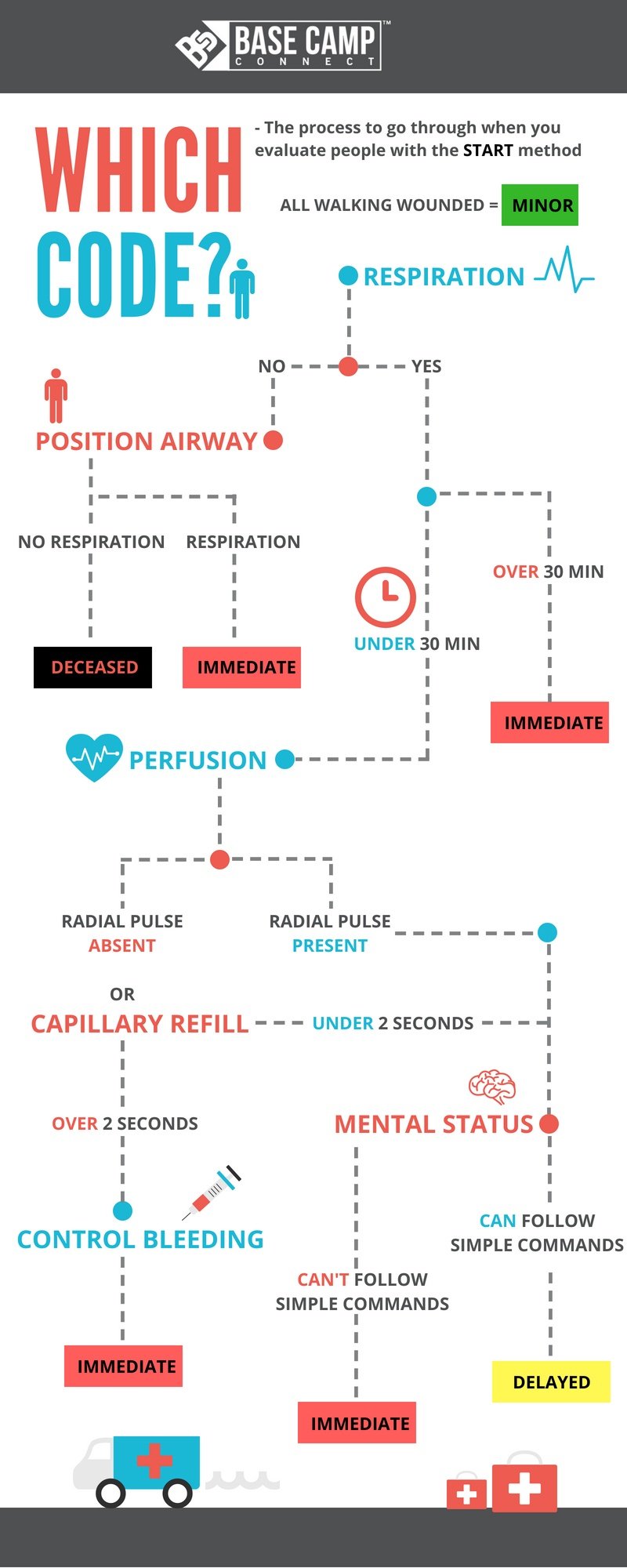

An Engine arrives as your team begins START (Simple Triage and Rapid Treatment). START Triage consists of quickly assessing physical and mental status parameters in a patient and moving to the next. It’s fast (no more than 30 seconds per patient) and targeted (Breathing? Y/N?), Mental Status (Alert?). Colored tags are placed on the patients after a rapid assessment to assess life threats. Black = Deceased; Red = Critical; Yellow: Delayed; Green: Ambulatory, transport can wait until others have been transported. I know what you’re thinking. Simple triage has emerged as a massive educational component, slides and educational resources are available to you as part of certification processes that we never imagined decades ago. You can specialize in this topic and discover that responders of all types, military, Federal, civilian, have developed excellent visual tools for START. And it’s been amazing how much we have learned. The guidelines have been revised several times as we have learned from disaster management. And whether you’re Military, Fire, Civilian, Law Enforcement, Hospital, or equipment manufacturers who keep the system going we are all necessary. Put us in a room together to learn a new skill or tool, and it’s quite entertaining. I would never dream of that. I noticed that we had created so many incredible visual graphs and quick-reference charts that there is no end to what is available on START…or JumpSTART…and everything in between. Perhaps with all of our neat colored charts, and rapid rollouts, and recertifications, and tailoring, there is a quiet person out there who pauses and says, “I need a minute.” It’s OK. It’s good. I smile about it. I remember continuing education with Military medics who were bold and brilliant. And it was striking to me that there were differences in the tools we used. That was then. It’s an incredible thing to stand back and see the evolution of triage and charts and the challenges that through all the charting, the concepts are very much aligned. Yes, we’ve seen that too. I’m not presenting the hundreds of incredible START charts. I’m taking that extra moment for us to have a scene together for the quiet ones who need a minute and the bold ones who know the value of taking a minute.

Although scene safety is not described in detail in rapid triage scenarios, a basic understanding that threat level to responders in all scenes, at all times, is always critical. Parameters of rapid triage are not difficult to commit to memory. The algorithm of R-P-M, or Respirations-Pulse-Mental Status, captures the critical elements of START.

The first step of START is to clear the area of patients who are ambulatory very quickly. Approaching patients who are leaning against walls, alert, lying with eyes open and looking around, possibly showing signs of traumatic injury but standing near others who may be critically injured, you would quickly be able to determine who can speak to you. Asking patients to stand and walk to a designated area, an awaiting emergency vehicle, or another building would be examples of how to quickly clear ambulatory patients.

“Sir/Madam, can you stand up and walk with me?”

If they comply, we marked these patients with a GREEN tag (or Priority 3 in a ranking of 0-3. With 0 being the patient who cannot be saved on site, and 3 being a patient similar to the type we just described, able to stand, ambulate, comply with instructions, and importantly, clear the area for assessment of additional patients. Remember in rapid triage assessments, and mass casualty incidents, an apneic patient, is not leaving. And so in START, begin with the R in the R-P-M of Respiratory-Pulse-Mental status.”What is the respiratory status of this patient?”

A single attempt to secure a patent airway is appropriate. If that fails to produce breathing, this patient is marked with a BLACK tag (Priority 0). Responders then move to the adjacent patient. The impact of encountering a BLACK tag patient and having to leave them and move quickly to someone next to them is not lost on anyone who has worked in the field. In rescue, today, we understand it is essential to review the impact of responding to these types of scenes with this type of patient, en masse. Though not designed to be part of START guidelines, the higher intent of information sharing is to understand that guidelines are intended to guide for a specific response, and it is assumed that responders require a support network afterward.

“The patient just took a breath.”

An apneic patient who subsequently breathes after the attempt to open the airway would be an extremely critical patient. This patient is marked with a RED tag (Priority 1). In START, this would be an extremely critical patient. When on a site where many patients require quick assessment, the red tag patient will need several fast decisions:

1. What is the respiratory effort of this patient?

If the rate is above 30 breaths per minute, the patient remains a RED tag.

2. Is this patient breathing but has no pulse?

This patient also remains a RED tag.

3. Is this patient breathing, has a pulse, and capillary refill is less than 2 seconds? If so, you have a directional shift to the next part of START: R-P-M (Mental Status).

After done all previous steps in rapid succession, if the patient is ALERT (“Sir/Madam, open your eyes.”), this patient can be moved to a scenario of lower acuity (YELLOW tag). If the patient is not alert, they remain a RED tag.

To bring real-time practice into any scenario, two high-impact interventions would be worthy of note in today’s scenes. The campaign of public awareness of CPR in earlier years (A-B-C, or Airway-Breathing-Circulation), resulting in the general public being active in initiating CPR, is to be lauded. The current movement of more “high quality” CPR, deeper compressions, “reperfusion first” efforts with a flow to the brain, minimal interruption of compressions when rapidly initiating AED rhythm efforts have anecdotally realigned the A-B-C algorithm to C-A-B. When given the opportunity on any scene, high-quality CPR should not be traded.

More excitedly, EMS and Fire, in conjunction with Law Enforcement, have done a marvelous job over the last few years refocusing urgency of patient care on controlling hemorrhage. This practice has been adopted and introduced into all types of first responders. The reemergence of the use of tourniquets in civilian EMS over the last several years has been a rapidly evolving intervention.

Both considerations just presented (High-Quality CPR and the refocus of arresting hemorrhage via the use of tourniquets) apply to patient care in a scene that allows for more time and more focused interventions. Even if current awareness and sharing of practice are not part of START, this is how we become better.

And that brings us back to START.

Remember, it’s fast (no more than 30 seconds per patient), it’s focused (R-P-M) Respiration, Pulse, Mental Status, and its applicability to scene response. Quickly clear who you can to save as many lives as you can, including your own, never, forget that.

Be safe.

START (Simple Triage and Rapid Treatment), Newport Beach Fire Department and Hoag Hospital, Newport Beach, CA, USA 1983.

Incident Command Training System, Emergency Management Institute, FEMA, US Department of Homeland Security (May 2008).

NIMS (National Incident Management System), FEMA, US Department of Homeland Security, (November 2017).